Earlier this week, iconic American filmmaker David Lynch died, leaving behind an astonishingly brilliant and bizarre body of work that blends violence, romance, mystery, surrealism, and classic Hollywood panache into a style that no other director has matched. And within that body of work is a whole bunch of scenes that you’ve probably played on YouTube for an unsuspecting friend, prefacing the viewing with “Dude, you gotta see this, it’s so fucked up!” In honor of Lynch’s life and work, let’s look back at the ten weirdest, funniest, most disturbing examples:

10. Coffee Table Head Slice (Lost Highway, 1997)

Not only does Pete get to make out with Patricia Arquette, but when they’re ambushed by Andy (Michael Massee), he executes a flawless WWE-style rolling kick-throw that launches Andy across the room. Unfortunately, there’s a glass coffee table in the middle of that room, which pretty much perfectly bisects his head. In keeping with the typical Lynchian aesthetic, Pete and Alice examine this tableau with little more than bemused curiosity.

Not only does Pete get to make out with Patricia Arquette, but when they’re ambushed by Andy (Michael Massee), he executes a flawless WWE-style rolling kick-throw that launches Andy across the room. Unfortunately, there’s a glass coffee table in the middle of that room, which pretty much perfectly bisects his head. In keeping with the typical Lynchian aesthetic, Pete and Alice examine this tableau with little more than bemused curiosity.

9. Shooting the Phantom (Inland Empire, 2006)

So you’ve just endured almost 3 hours of arthouse experimental horror insanity? Here’s some jumpscare nightmare fuel to send you home in a state of paralytic anxiety.

So you’ve just endured almost 3 hours of arthouse experimental horror insanity? Here’s some jumpscare nightmare fuel to send you home in a state of paralytic anxiety.

8. Laura Palmer’s Death (Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, 1992)

After countless slasher flicks throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s gave us all kinds of ways that popular blonde girls could be killed, Lynch outclasses them all with a scene that is genuinely touching, emotionally gutwrenching, and terrifying. The cry of “Please don’t make me do this!” will stick with you for quite a while.

After countless slasher flicks throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s gave us all kinds of ways that popular blonde girls could be killed, Lynch outclasses them all with a scene that is genuinely touching, emotionally gutwrenching, and terrifying. The cry of “Please don’t make me do this!” will stick with you for quite a while.

7. Willem DaFoe’s Head (Wild at Heart, 1990)

After one of the most unsettling scenes of sexual assault in cinema history, Bobby Peru pulls a heist with Sailor in which he shoots two store clerks and then prepares to kill Sailor as well. Then he gets into a firefight with a sheriff’s deputy, somehow falls to his knees with his own shotgun jammed into his neck, and, well, remember Sub-Zero’s fatality in the OG “Mortal Kombat” game? The next few seconds are basically that.

After one of the most unsettling scenes of sexual assault in cinema history, Bobby Peru pulls a heist with Sailor in which he shoots two store clerks and then prepares to kill Sailor as well. Then he gets into a firefight with a sheriff’s deputy, somehow falls to his knees with his own shotgun jammed into his neck, and, well, remember Sub-Zero’s fatality in the OG “Mortal Kombat” game? The next few seconds are basically that.

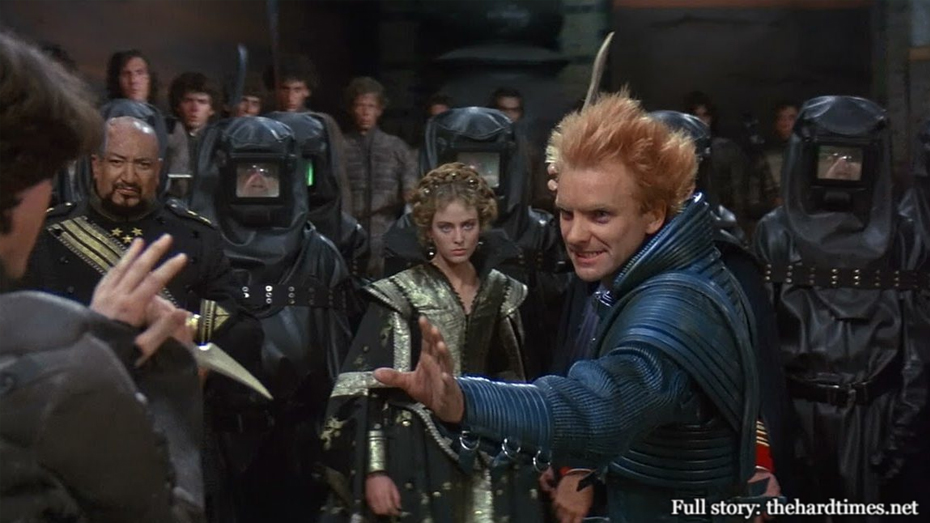

6. All of Dune (1984)

The entire movie is messed up, though not in the same sort of existential freak-out way that Lynch’s other films are. More in a “Wow, people actually spent creative energy and money to make this movie, that’s a shame” sort of way.

The entire movie is messed up, though not in the same sort of existential freak-out way that Lynch’s other films are. More in a “Wow, people actually spent creative energy and money to make this movie, that’s a shame” sort of way.

5. Welcome to Lumberton (Blue Velvet, 1986)

In a tight 2 minutes, the opening sequence to Lynch’s masterpiece puts across a pretty well-trodden idea: Beneath the placid surface of Anytown USA, dark and anti-social forces lurk, just waiting to infest all that is good and righteous. It’s a cliché premise that’s been explored in cinema from Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt” to “American Beauty,” but nobody does it quite like Lynch. With nothing but a montage of oversaturated images and a Bobby Vinton song, this scene not only introduces the theme of the entire film, but subtly suggests that the people on the “good” side of this duality are unknowingly empowering the dark side. And all this before Kyle MacLachlan even finds that ear.

In a tight 2 minutes, the opening sequence to Lynch’s masterpiece puts across a pretty well-trodden idea: Beneath the placid surface of Anytown USA, dark and anti-social forces lurk, just waiting to infest all that is good and righteous. It’s a cliché premise that’s been explored in cinema from Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt” to “American Beauty,” but nobody does it quite like Lynch. With nothing but a montage of oversaturated images and a Bobby Vinton song, this scene not only introduces the theme of the entire film, but subtly suggests that the people on the “good” side of this duality are unknowingly empowering the dark side. And all this before Kyle MacLachlan even finds that ear.

4. The Horrific Figure in the Alley (Mulholland Dr., 2001)

Even the first time you see the movie, you know it’s coming. Two men in Winkie’s Diner literally just discussed a nightmare about how fear leads to more fear, and how that fear is, naturally enough, wielded by a filthy man who hides in the dumpster behind Winkie’s, and as they leave the diner to see if the man is real, every single aspect of the cinematography tells you a jumpscare is coming, and then, sure as shootin’, it comes, but you still jump a mile and shriek like a toddler.

Even the first time you see the movie, you know it’s coming. Two men in Winkie’s Diner literally just discussed a nightmare about how fear leads to more fear, and how that fear is, naturally enough, wielded by a filthy man who hides in the dumpster behind Winkie’s, and as they leave the diner to see if the man is real, every single aspect of the cinematography tells you a jumpscare is coming, and then, sure as shootin’, it comes, but you still jump a mile and shriek like a toddler.

3. The Mystery Man (Lost Highway, 1997)

Robert Blake’s first appearance at a distinctively Lynchian party in the Hollywood Hills makes for one of those scenes that sort of splits the difference between funny and terrifying. Sure, he freaks out Fred with the ol’ “I’m both here and at your house at once!” parlor trick, and it’s creepy, but he still seems like an affable fellow. But when he appears in a VHS shot along with Fred’s murdered wife a little later? You’re gonna need a minute.

Robert Blake’s first appearance at a distinctively Lynchian party in the Hollywood Hills makes for one of those scenes that sort of splits the difference between funny and terrifying. Sure, he freaks out Fred with the ol’ “I’m both here and at your house at once!” parlor trick, and it’s creepy, but he still seems like an affable fellow. But when he appears in a VHS shot along with Fred’s murdered wife a little later? You’re gonna need a minute.

2. Voyeurism in the Closet (Blue Velvet, 1986)

So you found out your friend hasn’t seen “Blue Velvet,” and you were like “Dude! You haven’t seen ‘Blue Velvet’?! That’s crazy, we gotta watch it right now!” and it’s going pretty well until the scene where Jeffrey spies on Dorothy and Frank while they do their whole non-consensual BDSM with amyl nitrate in a gas mask thing, and suddenly your friend is looking at you like you’re a psychopath for owning this movie, and all your protestations about how it’s the greatest art film of the 1980s and was basically Lynch’s redemption project after “Dune” shit the bed can’t make up for the fact that you just made your buddy sit through one of the most depraved scenes ever put on film.

So you found out your friend hasn’t seen “Blue Velvet,” and you were like “Dude! You haven’t seen ‘Blue Velvet’?! That’s crazy, we gotta watch it right now!” and it’s going pretty well until the scene where Jeffrey spies on Dorothy and Frank while they do their whole non-consensual BDSM with amyl nitrate in a gas mask thing, and suddenly your friend is looking at you like you’re a psychopath for owning this movie, and all your protestations about how it’s the greatest art film of the 1980s and was basically Lynch’s redemption project after “Dune” shit the bed can’t make up for the fact that you just made your buddy sit through one of the most depraved scenes ever put on film.

1. Visiting Mary’s Parents (Eraserhead, 1977)

There’s really not a single scene in this movie that isn’t deeply unsettling to the point of making you feel vaguely violated and dirty. The smash cut to the baby covered in sores? The Vaudeville-on-acid spectacle of the Girl in the Radiator? Henry being decapitated by the giant phallic parasite thing that apparently lives inside him? All good candidates for number 1, but for our money it’s the long sequence in which Henry visits his girlfriend Mary and her deranged parents, only to be slapped with paternal responsibility for the infamously inhuman “Eraserhead Baby.” Whether it’s Mary’s out-of-nowhere seizure that doesn’t even stop Henry from talking about his job as a printer, or Mary’s mother’s attempt to make out with him, or her making a salad by manipulating a comatose old woman’s hands like a marionette, or the giant parody of a grin on Mary’s father’s face as he talks about being a plumber, this scene is offputting in a way you can feel in your bones. But it’s the carving of the homemade chickens that will really stick with you. Lynch’s career-long fascination with the intertwined dynamics of the organic and the mechanical really comes home to roost (as it were) in this immortal moment of surrealist indie filmmaking.

There’s really not a single scene in this movie that isn’t deeply unsettling to the point of making you feel vaguely violated and dirty. The smash cut to the baby covered in sores? The Vaudeville-on-acid spectacle of the Girl in the Radiator? Henry being decapitated by the giant phallic parasite thing that apparently lives inside him? All good candidates for number 1, but for our money it’s the long sequence in which Henry visits his girlfriend Mary and her deranged parents, only to be slapped with paternal responsibility for the infamously inhuman “Eraserhead Baby.” Whether it’s Mary’s out-of-nowhere seizure that doesn’t even stop Henry from talking about his job as a printer, or Mary’s mother’s attempt to make out with him, or her making a salad by manipulating a comatose old woman’s hands like a marionette, or the giant parody of a grin on Mary’s father’s face as he talks about being a plumber, this scene is offputting in a way you can feel in your bones. But it’s the carving of the homemade chickens that will really stick with you. Lynch’s career-long fascination with the intertwined dynamics of the organic and the mechanical really comes home to roost (as it were) in this immortal moment of surrealist indie filmmaking.